You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Σε τούτα εδώ τα μάρμαρα

- Thread starter anef

- Start date

Από το δεύτερο βιβλίο, την Ευτέρπη:

96. τὰ δὲ δὴ πλοῖά σφι, τοῖσι φορτηγέουσι, ἐστὶ ἐκ τῆς ἀκάνθης ποιεύμενα, τῆς ἡ μορφὴ μὲν ἐστὶ ὁμοιοτάτη τῷ Κυρηναίῳ λωτῷ, τὸ δὲ δάκρυον κόμμι ἐστί. ἐκ ταύτης ὦν τῆς ἀκάνθης κοψάμενοι ξύλα ὅσον τε διπήχεα πλινθηδὸν συντιθεῖσι ναυπηγεύμενοι τρόπον τοιόνδε· [2] περὶ γόμφους πυκνοὺς καὶ μακροὺς περιείρουσι τὰ διπήχεα ξύλα· ἐπεὰν δὲ τῷ τρόπῳ τούτῳ ναυπηγήσωνται, ζυγὰ ἐπιπολῆς τείνουσι αὐτῶν· νομεῦσι δὲ οὐδὲν χρέωνται· ἔσωθεν δὲ τὰς ἁρμονίας ἐν ὦν ἐπάκτωσαν τῇ βύβλῳ. [3] πηδάλιον δὲ ἓν ποιεῦνται, καὶ τοῦτο διὰ τῆς τρόπιος διαβύνεται. ἱστῷ δὲ ἀκανθίνῳ χρέωνται, ἱστίοισι δὲ βυβλίνοισι. ταῦτα τὰ πλοῖα ἀνὰ μὲν τὸν ποταμὸν οὐ δύναται πλέειν, ἢν μὴ λαμπρὸς ἄνεμος ἐπέχῃ, ἐκ γῆς δὲ παρέλκεται, κατὰ ῥόον δὲ κομίζεται ὧδε· [4] ἔστι ἐκ μυρίκης πεποιημένη θύρη, κατερραμμένη ῥιπὶ καλάμων, καὶ λίθος τετρημένος διτάλαντος μάλιστά κῃ σταθμόν· τούτων τὴν μὲν θύρην δεδεμένην κάλῳ ἔμπροσθε τοῦ πλοίου ἀπιεῖ ἐπιφέρεσθαι, τὸν δὲ λίθον ἄλλῳ κάλῳ ὄπισθε. [5] ἡ μὲν δὴ θύρη τοῦ ῥόου ἐμπίπτοντος χωρέει ταχέως καὶ ἕλκει τὴν βᾶριν (τοῦτο γὰρ δὴ οὔνομα ἐστὶ τοῖσι πλοίοισι τούτοισι), ὁ δὲ λίθος ὄπισθε ἐπελκόμενος καὶ ἐὼν ἐν βυσσῷ κατιθύνει τὸν πλόον. ἔστι δέ σφι τὰ πλοῖα ταῦτα πλήθεϊ πολλά, καὶ ἄγει ἔνια πολλὰς χιλιάδας ταλάντων.

Σε μετάφραση του George Rawlinson:

The vessels used in Egypt for the transport of merchandise are made of the Acantha (Thorn), a tree which in its growth is very like the Cyrenaic lotus, and from which there exudes a gum. They cut a quantity of planks about two cubits in length from this tree, and then proceed to their ship-building, arranging the planks like bricks, and attaching them by ties to a number of long stakes or poles till the hull is complete, when they lay the cross-planks on the top from side to side. They give the boats no ribs, but caulk the seams with papyrus on the inside. Each has a single rudder, which is driven straight through the keel. The mast is a piece of acantha-wood, and the sails are made of papyrus. These boats cannot make way against the current unless there is a brisk breeze; they are, therefore, towed up-stream from the shore: down-stream they are managed as follows. There is a raft belonging to each, made of the wood of the tamarisk, fastened together with a wattling of reeds; and also a stone bored through the middle about two talents in weight. The raft is fastened to the vessel by a rope, and allowed to float down the stream in front, while the stone is attached by another rope astern. The result is that the raft, hurried forward by the current, goes rapidly down the river, and drags the "baris" (for so they call this sort of boat) after it; while the stone, which is pulled along in the wake of the vessel, and lies deep in the water, keeps the boat straight. There are a vast number of these vessels in Egypt, and some of them are of many thousand talents' burthen.

96. τὰ δὲ δὴ πλοῖά σφι, τοῖσι φορτηγέουσι, ἐστὶ ἐκ τῆς ἀκάνθης ποιεύμενα, τῆς ἡ μορφὴ μὲν ἐστὶ ὁμοιοτάτη τῷ Κυρηναίῳ λωτῷ, τὸ δὲ δάκρυον κόμμι ἐστί. ἐκ ταύτης ὦν τῆς ἀκάνθης κοψάμενοι ξύλα ὅσον τε διπήχεα πλινθηδὸν συντιθεῖσι ναυπηγεύμενοι τρόπον τοιόνδε· [2] περὶ γόμφους πυκνοὺς καὶ μακροὺς περιείρουσι τὰ διπήχεα ξύλα· ἐπεὰν δὲ τῷ τρόπῳ τούτῳ ναυπηγήσωνται, ζυγὰ ἐπιπολῆς τείνουσι αὐτῶν· νομεῦσι δὲ οὐδὲν χρέωνται· ἔσωθεν δὲ τὰς ἁρμονίας ἐν ὦν ἐπάκτωσαν τῇ βύβλῳ. [3] πηδάλιον δὲ ἓν ποιεῦνται, καὶ τοῦτο διὰ τῆς τρόπιος διαβύνεται. ἱστῷ δὲ ἀκανθίνῳ χρέωνται, ἱστίοισι δὲ βυβλίνοισι. ταῦτα τὰ πλοῖα ἀνὰ μὲν τὸν ποταμὸν οὐ δύναται πλέειν, ἢν μὴ λαμπρὸς ἄνεμος ἐπέχῃ, ἐκ γῆς δὲ παρέλκεται, κατὰ ῥόον δὲ κομίζεται ὧδε· [4] ἔστι ἐκ μυρίκης πεποιημένη θύρη, κατερραμμένη ῥιπὶ καλάμων, καὶ λίθος τετρημένος διτάλαντος μάλιστά κῃ σταθμόν· τούτων τὴν μὲν θύρην δεδεμένην κάλῳ ἔμπροσθε τοῦ πλοίου ἀπιεῖ ἐπιφέρεσθαι, τὸν δὲ λίθον ἄλλῳ κάλῳ ὄπισθε. [5] ἡ μὲν δὴ θύρη τοῦ ῥόου ἐμπίπτοντος χωρέει ταχέως καὶ ἕλκει τὴν βᾶριν (τοῦτο γὰρ δὴ οὔνομα ἐστὶ τοῖσι πλοίοισι τούτοισι), ὁ δὲ λίθος ὄπισθε ἐπελκόμενος καὶ ἐὼν ἐν βυσσῷ κατιθύνει τὸν πλόον. ἔστι δέ σφι τὰ πλοῖα ταῦτα πλήθεϊ πολλά, καὶ ἄγει ἔνια πολλὰς χιλιάδας ταλάντων.

Σε μετάφραση του George Rawlinson:

The vessels used in Egypt for the transport of merchandise are made of the Acantha (Thorn), a tree which in its growth is very like the Cyrenaic lotus, and from which there exudes a gum. They cut a quantity of planks about two cubits in length from this tree, and then proceed to their ship-building, arranging the planks like bricks, and attaching them by ties to a number of long stakes or poles till the hull is complete, when they lay the cross-planks on the top from side to side. They give the boats no ribs, but caulk the seams with papyrus on the inside. Each has a single rudder, which is driven straight through the keel. The mast is a piece of acantha-wood, and the sails are made of papyrus. These boats cannot make way against the current unless there is a brisk breeze; they are, therefore, towed up-stream from the shore: down-stream they are managed as follows. There is a raft belonging to each, made of the wood of the tamarisk, fastened together with a wattling of reeds; and also a stone bored through the middle about two talents in weight. The raft is fastened to the vessel by a rope, and allowed to float down the stream in front, while the stone is attached by another rope astern. The result is that the raft, hurried forward by the current, goes rapidly down the river, and drags the "baris" (for so they call this sort of boat) after it; while the stone, which is pulled along in the wake of the vessel, and lies deep in the water, keeps the boat straight. There are a vast number of these vessels in Egypt, and some of them are of many thousand talents' burthen.

Δεν είμαι ικανός βέβαια να σχολιάσω καν, αλλά το βιβλίο της θα το ψάξω.

Ελένη Γλύκατζη Αρβελέρ: Στον τάφο στη Βεργίνα είναι θαμμένος ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος, όχι ο Φίλιππος

Ελένη Γλύκατζη Αρβελέρ: Στον τάφο στη Βεργίνα είναι θαμμένος ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος, όχι ο Φίλιππος

Εντόπισαν την ... πίστα χορού(!) της Σαλώμης

Με αυτές τις λέξεις προσπάθησε να μεταφράσει η συμπαθής ελληνικη εφημερίδα το dance floor where Salome's dance was performed.

Έκανε κι ένα λάθος ανήκεστης άγνοιας: Machaerus, το οχυρό (και μαζί παλάτι) του Ηρώδη, λεγόταν Μαχαιρούς (θηλυκό μάλλον, αλλά και αρσενικό), όχι *Μάχαιρος. Ο δε επικεφαλής της ανασκαφής αρχαιολόγος Győző Vörös μάλλον δεν προφέρεται *Γκιζζ Βορς.

Αυτό είναι το περίφημο δάπεδο, μπροστά στον θρόνο του Ηρώδη Αντίπα.

Αντίπας είπα; ??? Εμπρός! Όλα τα μωρά στην πίστα!!!

Κι αυτή είναι μια καλλιτεχνική αναπαράσταση.

Με αυτές τις λέξεις προσπάθησε να μεταφράσει η συμπαθής ελληνικη εφημερίδα το dance floor where Salome's dance was performed.

Έκανε κι ένα λάθος ανήκεστης άγνοιας: Machaerus, το οχυρό (και μαζί παλάτι) του Ηρώδη, λεγόταν Μαχαιρούς (θηλυκό μάλλον, αλλά και αρσενικό), όχι *Μάχαιρος. Ο δε επικεφαλής της ανασκαφής αρχαιολόγος Győző Vörös μάλλον δεν προφέρεται *Γκιζζ Βορς.

Αυτό είναι το περίφημο δάπεδο, μπροστά στον θρόνο του Ηρώδη Αντίπα.

Αντίπας είπα; ??? Εμπρός! Όλα τα μωρά στην πίστα!!!

Κι αυτή είναι μια καλλιτεχνική αναπαράσταση.

Γκέζε Βέρες (όλα τα ο είναι με umlaut -oe-, τα φωνήεντα με τους τόνους είναι πιο μακρά, το τελικό s είναι παχύ - το απλό s γράφεται sz όπως στο Görögország, Γκέρεγκορσαγκ, Ελλάδα --στα ουγγαρέζικα τονίζεται πάντα η πρώτη συλλαβή).Ο δε επικεφαλής της ανασκαφής αρχαιολόγος Győző Vörös μάλλον δεν προφέρεται *Γκιζζ Βορς.

Νέες ανακαλύψεις στην Πομπηία

Marcus Venerius Secundio = Μάρκος Βενέριος Σεκουνδίων

pompeiisites.org

pompeiisites.org

Marcus Venerius Secundio = Μάρκος Βενέριος Σεκουνδίων

The tomb of Marcus Venerius Secundio discovered at Porta Sarno with mummified human remains - Pompeii Sites

Mummified remains, along with the hair and bones of an individual buried in an ancient tomb have been found at the necropolis of Porta Sarno, to the east of the … keep it going

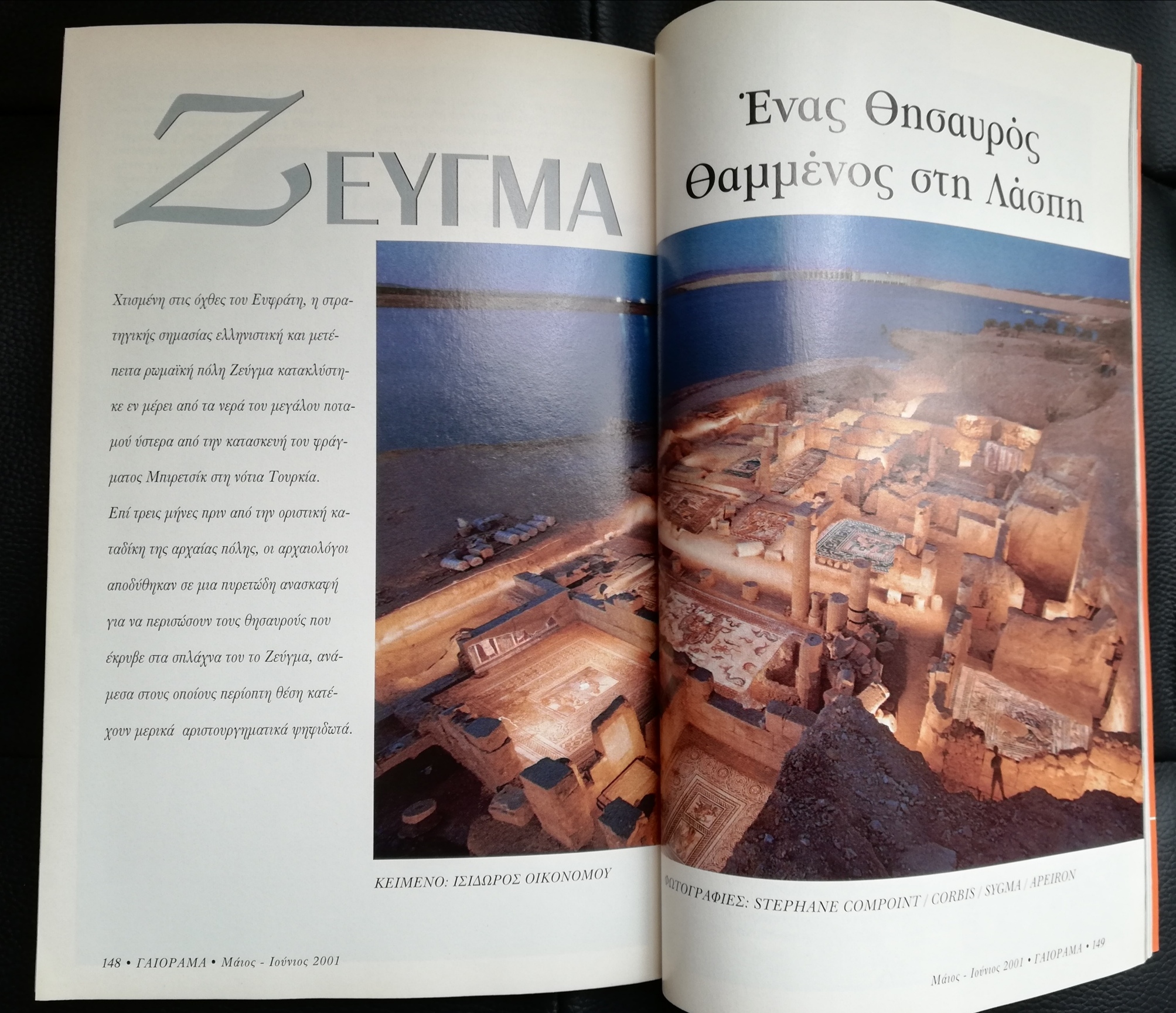

Ίσως το πιο σιγουράκι απ' όλα τα κλίκμπεϊτ για τα ελληνικά έντυπα, ιδίως της διασποράς, και την προεξασφαλισμένη ιοτροπία στα σόσιαλ το Ζεύγμα, δεν περνά μήνας να μην έχει και τη δημοσίευσή του (είδα στο Greek Reporter 30.12.2021, στο Greek Gateway 8.2.2022...).Έξοχα! Οι ελληνικές εφημερίδες ανακάλυψαν το Ζεύγμα. Ετούτη εδώ παραθέτει στοιχεία δίχως κανένα χρονικό προσδιορισμό, αφήνοντας τους αναγνώστες με την πλανημένη ιδέα ότι πρόκειται για πρόσφατη ανακάλυψη. Διόλου δεν είναι έτσι. Το Ζεύγμα ανασκάπτεται από το 1987 μέχρι σήμερα κατά κύματα, και μάλιστα όσο πλησίαζε το 2000 οι σωστικές ανασκαφές γίνονταν με πυρετώδη ρυθμό, για να προλάβουν την άνοδο της στάθμης του νερού από το φράγμα του Μπιρετζίκ που κατασκευαζόταν τότε (το φράγμα άρχισε εκείνη τη χρονιά να λειτουργεί και τελικά βύθισε μεγάλο μέρος της πόλης). Ο Ωκεανός και η Τηθύς ανακαλύφθηκαν το 1999, ενώ οι Μούσες το 2007 (άσχετο αν εμείς δεν έχουμε ακούσει τίποτε γι’ αυτά από το σοβαρό μας έντυπο και ηλεκτρονικό τύπο).

Υ.Γ. Φαίνεται πως το κύμα άρχισε από αυτήν εδώ την «είδηση»: Εξαιρετικής ωραιότητας είναι τα τρία ψηφιδωτά που έφερε τις τελευταίες μέρες στο φως η αρχαιολογική σκαπάνη στα τουρκικά σύνορα με τη Συρία.

Με παραξένεψε κι εμένα η είδηση, επειδή τυχαίνει να διάβασα μικρός για το Ζεύγμα και μου έμεινε.

Last edited:

Thought Lost in WW2, Records Discovery Reveals Secrets of Ancient People

by Aristos Georgiou, Science and Health Reporter of Newsweek (Newsweek, January 8, 2024)

Και η ελληνική του μετάφραση εδώ:

Εντοπίστηκαν ιστορικά αρχεία που θεωρούνταν χαμένα από τον Β’ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο – Αποκαλύπτουν μυστικά ενός αρχαίου λαού

Η ερευνήτρια του Πανεπιστημίου του Μάντσεστερ Τζένη Μέτκαλφ, Αιγυπτιολόγος με ειδίκευση στα βιοϊατρικά δεδομένα, ανακάλυψε τα αποτελέσματα μιας ανασκαφικής περιόδου από Άγγλους αρχαιολόγους στη Νουβία που θεωρούνταν χαμένα από τον Β΄ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο. Πρόκειται για Δελτία καταγραφής (recording cards) (και όχι *Κάρτες καταγραφής) των ευρημάτων από τις δύο πρώτες (από τέσσερις συνολικά) ανασκαφικές περιόδους σε νεκροταφεία της Κάτω Νουβίας, που έγιναν στις αρχές του 20ού αιώνα, και αποκαλύπτουν βιομετρικά δεδομένα για τους αρχαίους πληθυσμούς της χώρας αυτής, δεδομένα που οδηγούν σε συμπεράσματα για τις συνθήκες ζωής και τα έθιμα και τις αντιλήψεις των Νουβίων σε μεγάλη χρονική έκταση (από π.Χ. έως πολλούς αιώνες μετά).

by Aristos Georgiou, Science and Health Reporter of Newsweek (Newsweek, January 8, 2024)

Και η ελληνική του μετάφραση εδώ:

Εντοπίστηκαν ιστορικά αρχεία που θεωρούνταν χαμένα από τον Β’ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο – Αποκαλύπτουν μυστικά ενός αρχαίου λαού

Η ερευνήτρια του Πανεπιστημίου του Μάντσεστερ Τζένη Μέτκαλφ, Αιγυπτιολόγος με ειδίκευση στα βιοϊατρικά δεδομένα, ανακάλυψε τα αποτελέσματα μιας ανασκαφικής περιόδου από Άγγλους αρχαιολόγους στη Νουβία που θεωρούνταν χαμένα από τον Β΄ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο. Πρόκειται για Δελτία καταγραφής (recording cards) (και όχι *Κάρτες καταγραφής) των ευρημάτων από τις δύο πρώτες (από τέσσερις συνολικά) ανασκαφικές περιόδους σε νεκροταφεία της Κάτω Νουβίας, που έγιναν στις αρχές του 20ού αιώνα, και αποκαλύπτουν βιομετρικά δεδομένα για τους αρχαίους πληθυσμούς της χώρας αυτής, δεδομένα που οδηγούν σε συμπεράσματα για τις συνθήκες ζωής και τα έθιμα και τις αντιλήψεις των Νουβίων σε μεγάλη χρονική έκταση (από π.Χ. έως πολλούς αιώνες μετά).

Hidden story behind 2,000 bronze statue fragments unearthed in Izmir’s ancient 'junkyard'

By Koray Erdogan

Hidden story behind 2,000 bronze statue fragments unearthed in Izmir’s ancient 'junkyard' A view of statue fragments which are found during the excavation at the ancient city of Metropolis, which was used as a “junkyard,” in Izmir, Türkiye, January 9, 2025. Archaeologists in Türkiye’s Izmir have made a fascinating discovery at the ancient site of Metropolis—approximately 2,000 bronze statue fragments that could rewrite parts of the city’s history. These fragments, uncovered in an area believed to have served as an “ancient junkyard,” offer a unique glimpse into the cultural and religious shifts of the region during the Late Antiquity period.

What happened to bronze statue fragments of ancient Metropolis?

The fragments found at the Metropolis excavation site are believed to come from both Hellenistic and Roman-era statues, including parts of heads, eyes, fingers, and sandals. According to Professor Serdar Aybek, the excavation’s lead archaeologist from Dokuz Eylul University, these statues were likely dismantled and melted down during a pivotal time in history—the transition from polytheistic beliefs to monotheistic religions, particularly Christianity. As these ancient statues lost their religious significance, they were repurposed for other uses, primarily being recycled for their valuable bronze material.

Uncovering ancient recycling practices

What makes this discovery even more significant is the evidence of recycling practices that dates back over a thousand years. Along with the fragmented statues, archaeologists also found square and rectangular bronze plates, which were likely used in the casting and repair processes of statues. This suggests that Metropolis may have been a hub for bronze statue production or restoration during its peak.

Link to historical figures and benefactors

The bronze fragments may also provide clues about some of the city’s benefactors. Some of the statues could have been erected in honor of influential individuals, such as those mentioned in inscriptions like “Apollonios of Metropolis.” This connection adds a layer of historical context to the discovery, revealing the social and cultural dynamics of the city during ancient times.

What’s next for excavation?

The artifacts from Metropolis are now being carefully analyzed and conserved, shedding light on the region’s rich past. With over 11,000 artifacts, including ceramics, coins, and sculptures, already discovered at the site, this new find further enhances the historical value of Metropolis. Archaeologists and historians are eagerly anticipating what more the site has to offer as excavation continues.

Turkiye Today January 16, 2025

By Koray Erdogan

Hidden story behind 2,000 bronze statue fragments unearthed in Izmir’s ancient 'junkyard' A view of statue fragments which are found during the excavation at the ancient city of Metropolis, which was used as a “junkyard,” in Izmir, Türkiye, January 9, 2025. Archaeologists in Türkiye’s Izmir have made a fascinating discovery at the ancient site of Metropolis—approximately 2,000 bronze statue fragments that could rewrite parts of the city’s history. These fragments, uncovered in an area believed to have served as an “ancient junkyard,” offer a unique glimpse into the cultural and religious shifts of the region during the Late Antiquity period.

What happened to bronze statue fragments of ancient Metropolis?

The fragments found at the Metropolis excavation site are believed to come from both Hellenistic and Roman-era statues, including parts of heads, eyes, fingers, and sandals. According to Professor Serdar Aybek, the excavation’s lead archaeologist from Dokuz Eylul University, these statues were likely dismantled and melted down during a pivotal time in history—the transition from polytheistic beliefs to monotheistic religions, particularly Christianity. As these ancient statues lost their religious significance, they were repurposed for other uses, primarily being recycled for their valuable bronze material.

Uncovering ancient recycling practices

What makes this discovery even more significant is the evidence of recycling practices that dates back over a thousand years. Along with the fragmented statues, archaeologists also found square and rectangular bronze plates, which were likely used in the casting and repair processes of statues. This suggests that Metropolis may have been a hub for bronze statue production or restoration during its peak.

Link to historical figures and benefactors

The bronze fragments may also provide clues about some of the city’s benefactors. Some of the statues could have been erected in honor of influential individuals, such as those mentioned in inscriptions like “Apollonios of Metropolis.” This connection adds a layer of historical context to the discovery, revealing the social and cultural dynamics of the city during ancient times.

What’s next for excavation?

The artifacts from Metropolis are now being carefully analyzed and conserved, shedding light on the region’s rich past. With over 11,000 artifacts, including ceramics, coins, and sculptures, already discovered at the site, this new find further enhances the historical value of Metropolis. Archaeologists and historians are eagerly anticipating what more the site has to offer as excavation continues.

Turkiye Today January 16, 2025

cougr

¥

BOOKS

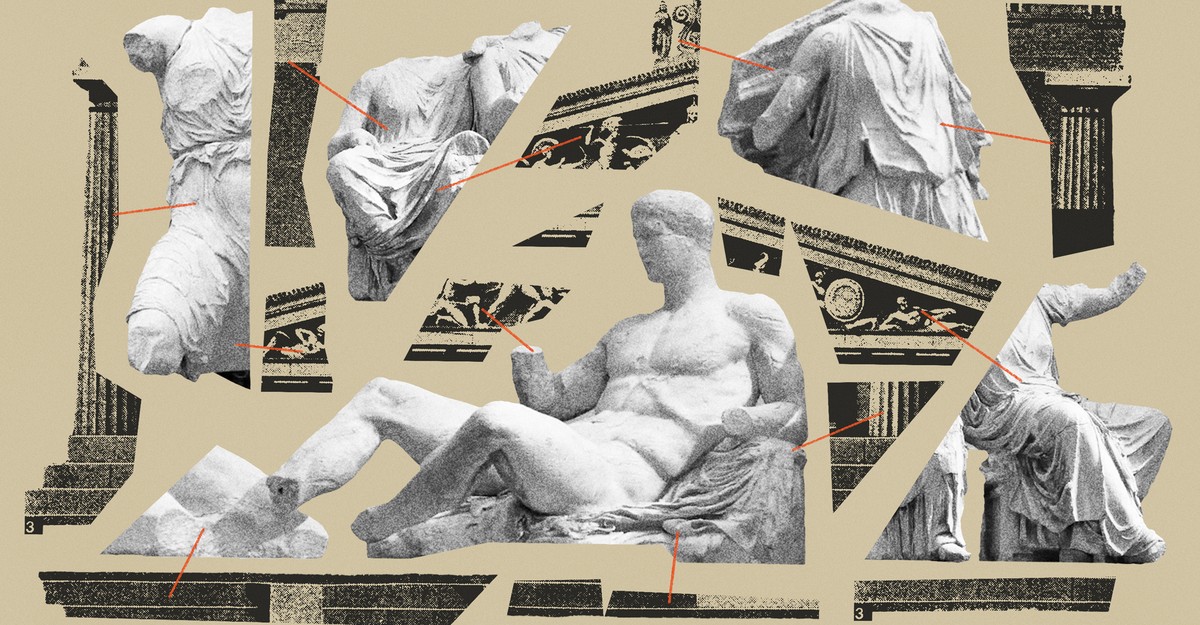

What Christopher Hitchens Understood About the Parthenon

The British Museum should return the ancient treasures to Greece for the sake of art, not nationalism.

By Ralph Leonard

FEBRUARY 4, 2025, 10:47 AM ET

Ever since the early 19th century, when Thomas Bruce, seventh earl of Elgin, sawed off and crowbarred many of the carvings that ringed the top of the Parthenon and sold them to the British Museum to dodge bankruptcy, the British have been sharply polarized over whether Britain or Greece has the right to these sculptures. For many liberals and radicals, beginning with Lord Byron, Elgin was a vandal who had committed sacrilege. Yet others maintained that he’d acquired the marbles legally, and even that he’d rescued them from inevitable neglect under the Ottoman empire.

In December, The Guardian reported that talks between the Greek government and the British Museum over the potential return of the Parthenon marbles were “well advanced.” Although a final agreement isn’t imminent, this development is significant. Negotiations have been under way for some time, built around an extended loan of the sculptures to Athens in return for the temporary transfer of some Greek treasures to Britain. The Starmer administration is more amenable to a final agreement than the previous government (though it won’t budge on a law that forbids the permanent removal of British Museum artifacts). After nearly two centuries of bitter but worthless wrangling, one of the longest-running cultural quarrels in Europe might soon be entering its epilogue.

For a long time, I was uncertain of my position on this question. On the one hand, it is a plain fact that imperialist powers have dispossessed many nations of much of their cultural patrimony. The present distribution of treasures in museums across the world reflects the global inequality in wealth and power—in favor of Europe and North America. So campaigns for repatriation of these objects are regarded as attempts to redress this imbalance, allowing the formerly colonized to reclaim their rightful property.

Many Greeks believe that this applies to them, too. Their argument is that the marbles are the property of the Greek nation, which freed itself from the Ottoman empire in 1832 after centuries of being its vassal. This seems self-evidently true—until you consider the British Museum’s counterargument, which is that there is great value in the encyclopedic museum: a place where the heritage of many ancient civilizations can be seen, emphasizing the interconnectedness of humanity. In this framing, returning the marbles would be reactionary and nationalist; retaining them is progressive and cosmopolitan. Similar debates have shot through the many battlefronts of the culture wars, such as identity politics and the debate over what books belong in the canon. Does art belong to all of humanity, or is it fundamentally rooted in the particular culture in which it was produced?

Christopher Hitchens, among the most eloquent and forceful advocates of rejoining the Parthenon marbles, helped tilt me toward the cause of repatriation. With great timing, Verso Books has just reissued his slim book The Parthenon Marbles: The Case for Reunification. One of the earliest polemics by the notoriously pugilistic cultural critic, who died in 2011, it was originally published in 1987 under the title Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles and reissued once before, in 2008, under its current title. The renaming accorded with changing times (referring to the “Elgin marbles” was no longer politically correct); it also revealed a subtle evolution in the point that Hitchens wished to stress: namely, the aesthetic case for reattachment.

Hitchens’s dedication to this cause wasn’t merely due to a romantic philhellenism rooted in the classical British-private-school curriculum; his life was intertwined with the Hellenic world. As a young socialist and internationalist in the 1970s, he had written and spoken against the Greek military junta that had persecuted his fellow leftists. The independence of Cyprus was among his precious causes, alongside self-determination for the Kurds and the Palestinians—who had long been victims of occupation and imperialist power games. His first wife was a Greek Cypriot, and, as he noted movingly in his memoir Hitch-22, his mother died by suicide in a hotel room overlooking the Acropolis, amid a 1973 anti-junta student uprising. The cause of the Parthenon marbles was therefore both personal and political, emblematic “of a long and honourable solidarity between British liberals and radicals and the cause of a free and independent Greece,” as he wrote in the introduction to the 2008 edition.

And yet he makes his case for repatriating the works almost exclusively on artistic grounds. The argument is simple and, as Hitchens put it, “unanswerable.” One of the great monuments of world culture—a temple garlanded with masterful carvings—the Parthenon was designed by Phidias to celebrate the glory of Athens. Its friezes depict a procession of gods, warriors, and mythical animals; its metopes, single panels within the larger frieze, narrate mythological battles of the Athenians against the Amazonians and the Centaurs, alluding to the Greco-Persian wars. Most of these scenes were—and remain—amputated, disfigured, and scattered. For instance, the body of the goddess Iris is now in London, while her head is in Athens. Poseidon’s front torso is in Athens, the rear part in London. The cavalcade of galloping horsemen is crudely fragmented across several nations. The repair of this travesty, to the extent that it is possible, so that it can be aesthetically appreciated as a united whole, is long overdue.

Many of the anti-unification arguments Hitchens faced in the 1980s have aged badly—chief among them the assertion that Athens won’t be an adequate home for them because of instability, pollution, and a lack of infrastructure. Today it feels patronizing, because it is so obvious, to point out that Greece has been a stable modern democracy for more than 50 years, and that the state-of-the-art Acropolis Museum, opened in 2009, has proved that the Greeks are not just worthy, but superb custodians of their antiquity. Reattaching the marbles to the fragile ruins of the temple, whose roof was blown off by the Venetians in 1687, would be impossible. But within this spacious museum building, visible from the Acropolis, the reunited marbles would be protected against the elements, accessible to visitors, and mounted in the original order on a scale model of the Parthenon’s upper portion.

One retentionist argument, however, has endured, and it is of the slippery-slope variety: that reuniting the marbles will set off an avalanche of claims that every ancient artifact be returned to its land of origin, which together will abolish the very idea of the cosmopolitan museum. Hitchens once dismissed this line of reasoning as the “old last-ditch standby of the bureaucrat.” For one, he wrote sardonically, “there are no Assyrians, Hittites or Babylonians to take up the cry of ‘precedent.’”

Yet in the years following Hitchens’s death, this charge has accrued some credibility. European and American museums have been beset by campaigns to “decolonize” them. Some pieces, such as the Benin bronzes, ended up in these museums as loot from colonial smash-and-grabs much more brazen than Elgin’s exploits. Hence, the decolonizers argue, museums are symbols of cultural domination. Many of these campaigns have an ethnocentric dimension, in which the volksgeist of the art is placed above its aesthetic virtues. The example of the Benin bronzes represents the potential danger of such campaigns: The government of Nigeria, which encompasses the former kingdom of Benin, overruled a national commission that aimed to house the pieces in a new museum, decreeing instead that all repatriated bronzes are henceforth the personal property of a powerless potentate, the oba of Benin, who can do with them what he will.

So what makes the Parthenon sculptures different from the bronzes, which were also originally plundered by British colonialists? Can the conclusion that one claim is more valid than the other be ascribed to Western bias?

First, although some of the bronzes were part of a unified work depicting the history and mythology of the kingdom (which was annexed by the British empire in 1897), the majority are stand-alone pieces. People can admire the brilliance of the bracelets and statues as discrete objects whether in London, New York, or Lagos, and perhaps even more so when viewing them in relation to other cultures—because the bronzes themselves were a product of exchange with another culture, the Portuguese. Second, there is no danger of the Parthenon marbles being out of public view. As a general rule, our world’s culture should be accessible to as many people as possible. That means putting it in public museums, rather than the traditional palaces of ceremonial monarchs.

Hitchens was fond of saying of the marbles, “Picture the panel of the Mona Lisa, if it had been sawn in half.” In this hypothetical, any reunification of the Mona Lisa in any museum would do. It needn’t be in Florence, where it was painted. A more apt hypothetical might be: What if, during the British Raj, the dome of the Taj Mahal had been dismantled and detained in the British Museum? This isn’t a flippant analogy; during the Indian mutiny of 1857, British soldiers looted the Taj Mahal, removing rare gems and lapis lazuli. Decades later, Lord Curzon, then viceroy of India, had the good sense to restore it.

Everyone knows what a perversion fragmenting the Taj Mahal would be. We wouldn’t appreciate it with the awe we currently do as the “frozen music” (as Goethe once defined architecture) of Indo-Islamic design. We would be impatient to see what it would look like with its dome reattached—and in Agra, India, for only there can you properly see its marvelous proportions and appreciate the way the marble interacts with the light and the reflecting pools, changing hue depending on the time of day. This nearly magical experience couldn’t be re-created in, say, Manchester.

Whether as a testament to the Athenian enlightenment or Periclean imperialism, the Parthenon is a monument of civilization. For those of us who derive a humanist and democratic ethos from classical Athens, the temple matters greatly. In this sense, the marbles aren’t simply Greek, but belong to all of humanity. The case for reunification has to be made on this cosmopolitan basis. The world deserves to see the story that Phidias intended to tell in whole.

For decades, Greece has undertaken the painstaking work of conserving and restoring the Parthenon. Of course, the vicissitudes of history have left their irrevocable mark. The temple won’t literally be put back together like it once was; the Byzantines, Venetians, and Ottomans made sure of that. The closest I will ever come to seeing the Parthenon in its original, intact form is by playing Assassin’s Creed Odyssey on PlayStation, or visiting the replica Parthenon in Nashville (which is a bit of a Taj Mahal–in–Manchester experience). Nevertheless, thanks to the spacious Acropolis Museum, visitors could see the ruins of the temple and then the Parthenon marbles in the same afternoon. They could also appreciate the irony of the marbles depicting the glories of the Athenians while the temple itself bears the scars of multiple Greek defeats. That visible damage is part of the great and tragic narrative of this wonder, and always will be. And it can be truly appreciated only once the reunification has been accomplished.

Germany and Italy have already returned fragments from the Parthenon to Athens. Britain should do its part, out of an impulse toward restoration in the most generous sense. Hitchens, as he often did, got the tone just right:

“There is still time to make the act of restitution: not extorted by pressure or complaint but freely offered as a homage to the indivisibility of art and—why not say it without embarrassment?—of justice too.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ralph Leonard

Ralph Leonard is a British-Nigerian writer on international politics, religion, culture and humanism.

www.theatlantic.com

www.theatlantic.com

What Christopher Hitchens Understood About the Parthenon

The British Museum should return the ancient treasures to Greece for the sake of art, not nationalism.

By Ralph Leonard

FEBRUARY 4, 2025, 10:47 AM ET

Ever since the early 19th century, when Thomas Bruce, seventh earl of Elgin, sawed off and crowbarred many of the carvings that ringed the top of the Parthenon and sold them to the British Museum to dodge bankruptcy, the British have been sharply polarized over whether Britain or Greece has the right to these sculptures. For many liberals and radicals, beginning with Lord Byron, Elgin was a vandal who had committed sacrilege. Yet others maintained that he’d acquired the marbles legally, and even that he’d rescued them from inevitable neglect under the Ottoman empire.

In December, The Guardian reported that talks between the Greek government and the British Museum over the potential return of the Parthenon marbles were “well advanced.” Although a final agreement isn’t imminent, this development is significant. Negotiations have been under way for some time, built around an extended loan of the sculptures to Athens in return for the temporary transfer of some Greek treasures to Britain. The Starmer administration is more amenable to a final agreement than the previous government (though it won’t budge on a law that forbids the permanent removal of British Museum artifacts). After nearly two centuries of bitter but worthless wrangling, one of the longest-running cultural quarrels in Europe might soon be entering its epilogue.

For a long time, I was uncertain of my position on this question. On the one hand, it is a plain fact that imperialist powers have dispossessed many nations of much of their cultural patrimony. The present distribution of treasures in museums across the world reflects the global inequality in wealth and power—in favor of Europe and North America. So campaigns for repatriation of these objects are regarded as attempts to redress this imbalance, allowing the formerly colonized to reclaim their rightful property.

Many Greeks believe that this applies to them, too. Their argument is that the marbles are the property of the Greek nation, which freed itself from the Ottoman empire in 1832 after centuries of being its vassal. This seems self-evidently true—until you consider the British Museum’s counterargument, which is that there is great value in the encyclopedic museum: a place where the heritage of many ancient civilizations can be seen, emphasizing the interconnectedness of humanity. In this framing, returning the marbles would be reactionary and nationalist; retaining them is progressive and cosmopolitan. Similar debates have shot through the many battlefronts of the culture wars, such as identity politics and the debate over what books belong in the canon. Does art belong to all of humanity, or is it fundamentally rooted in the particular culture in which it was produced?

Christopher Hitchens, among the most eloquent and forceful advocates of rejoining the Parthenon marbles, helped tilt me toward the cause of repatriation. With great timing, Verso Books has just reissued his slim book The Parthenon Marbles: The Case for Reunification. One of the earliest polemics by the notoriously pugilistic cultural critic, who died in 2011, it was originally published in 1987 under the title Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles and reissued once before, in 2008, under its current title. The renaming accorded with changing times (referring to the “Elgin marbles” was no longer politically correct); it also revealed a subtle evolution in the point that Hitchens wished to stress: namely, the aesthetic case for reattachment.

Hitchens’s dedication to this cause wasn’t merely due to a romantic philhellenism rooted in the classical British-private-school curriculum; his life was intertwined with the Hellenic world. As a young socialist and internationalist in the 1970s, he had written and spoken against the Greek military junta that had persecuted his fellow leftists. The independence of Cyprus was among his precious causes, alongside self-determination for the Kurds and the Palestinians—who had long been victims of occupation and imperialist power games. His first wife was a Greek Cypriot, and, as he noted movingly in his memoir Hitch-22, his mother died by suicide in a hotel room overlooking the Acropolis, amid a 1973 anti-junta student uprising. The cause of the Parthenon marbles was therefore both personal and political, emblematic “of a long and honourable solidarity between British liberals and radicals and the cause of a free and independent Greece,” as he wrote in the introduction to the 2008 edition.

And yet he makes his case for repatriating the works almost exclusively on artistic grounds. The argument is simple and, as Hitchens put it, “unanswerable.” One of the great monuments of world culture—a temple garlanded with masterful carvings—the Parthenon was designed by Phidias to celebrate the glory of Athens. Its friezes depict a procession of gods, warriors, and mythical animals; its metopes, single panels within the larger frieze, narrate mythological battles of the Athenians against the Amazonians and the Centaurs, alluding to the Greco-Persian wars. Most of these scenes were—and remain—amputated, disfigured, and scattered. For instance, the body of the goddess Iris is now in London, while her head is in Athens. Poseidon’s front torso is in Athens, the rear part in London. The cavalcade of galloping horsemen is crudely fragmented across several nations. The repair of this travesty, to the extent that it is possible, so that it can be aesthetically appreciated as a united whole, is long overdue.

Many of the anti-unification arguments Hitchens faced in the 1980s have aged badly—chief among them the assertion that Athens won’t be an adequate home for them because of instability, pollution, and a lack of infrastructure. Today it feels patronizing, because it is so obvious, to point out that Greece has been a stable modern democracy for more than 50 years, and that the state-of-the-art Acropolis Museum, opened in 2009, has proved that the Greeks are not just worthy, but superb custodians of their antiquity. Reattaching the marbles to the fragile ruins of the temple, whose roof was blown off by the Venetians in 1687, would be impossible. But within this spacious museum building, visible from the Acropolis, the reunited marbles would be protected against the elements, accessible to visitors, and mounted in the original order on a scale model of the Parthenon’s upper portion.

One retentionist argument, however, has endured, and it is of the slippery-slope variety: that reuniting the marbles will set off an avalanche of claims that every ancient artifact be returned to its land of origin, which together will abolish the very idea of the cosmopolitan museum. Hitchens once dismissed this line of reasoning as the “old last-ditch standby of the bureaucrat.” For one, he wrote sardonically, “there are no Assyrians, Hittites or Babylonians to take up the cry of ‘precedent.’”

Yet in the years following Hitchens’s death, this charge has accrued some credibility. European and American museums have been beset by campaigns to “decolonize” them. Some pieces, such as the Benin bronzes, ended up in these museums as loot from colonial smash-and-grabs much more brazen than Elgin’s exploits. Hence, the decolonizers argue, museums are symbols of cultural domination. Many of these campaigns have an ethnocentric dimension, in which the volksgeist of the art is placed above its aesthetic virtues. The example of the Benin bronzes represents the potential danger of such campaigns: The government of Nigeria, which encompasses the former kingdom of Benin, overruled a national commission that aimed to house the pieces in a new museum, decreeing instead that all repatriated bronzes are henceforth the personal property of a powerless potentate, the oba of Benin, who can do with them what he will.

So what makes the Parthenon sculptures different from the bronzes, which were also originally plundered by British colonialists? Can the conclusion that one claim is more valid than the other be ascribed to Western bias?

First, although some of the bronzes were part of a unified work depicting the history and mythology of the kingdom (which was annexed by the British empire in 1897), the majority are stand-alone pieces. People can admire the brilliance of the bracelets and statues as discrete objects whether in London, New York, or Lagos, and perhaps even more so when viewing them in relation to other cultures—because the bronzes themselves were a product of exchange with another culture, the Portuguese. Second, there is no danger of the Parthenon marbles being out of public view. As a general rule, our world’s culture should be accessible to as many people as possible. That means putting it in public museums, rather than the traditional palaces of ceremonial monarchs.

Hitchens was fond of saying of the marbles, “Picture the panel of the Mona Lisa, if it had been sawn in half.” In this hypothetical, any reunification of the Mona Lisa in any museum would do. It needn’t be in Florence, where it was painted. A more apt hypothetical might be: What if, during the British Raj, the dome of the Taj Mahal had been dismantled and detained in the British Museum? This isn’t a flippant analogy; during the Indian mutiny of 1857, British soldiers looted the Taj Mahal, removing rare gems and lapis lazuli. Decades later, Lord Curzon, then viceroy of India, had the good sense to restore it.

Everyone knows what a perversion fragmenting the Taj Mahal would be. We wouldn’t appreciate it with the awe we currently do as the “frozen music” (as Goethe once defined architecture) of Indo-Islamic design. We would be impatient to see what it would look like with its dome reattached—and in Agra, India, for only there can you properly see its marvelous proportions and appreciate the way the marble interacts with the light and the reflecting pools, changing hue depending on the time of day. This nearly magical experience couldn’t be re-created in, say, Manchester.

Whether as a testament to the Athenian enlightenment or Periclean imperialism, the Parthenon is a monument of civilization. For those of us who derive a humanist and democratic ethos from classical Athens, the temple matters greatly. In this sense, the marbles aren’t simply Greek, but belong to all of humanity. The case for reunification has to be made on this cosmopolitan basis. The world deserves to see the story that Phidias intended to tell in whole.

For decades, Greece has undertaken the painstaking work of conserving and restoring the Parthenon. Of course, the vicissitudes of history have left their irrevocable mark. The temple won’t literally be put back together like it once was; the Byzantines, Venetians, and Ottomans made sure of that. The closest I will ever come to seeing the Parthenon in its original, intact form is by playing Assassin’s Creed Odyssey on PlayStation, or visiting the replica Parthenon in Nashville (which is a bit of a Taj Mahal–in–Manchester experience). Nevertheless, thanks to the spacious Acropolis Museum, visitors could see the ruins of the temple and then the Parthenon marbles in the same afternoon. They could also appreciate the irony of the marbles depicting the glories of the Athenians while the temple itself bears the scars of multiple Greek defeats. That visible damage is part of the great and tragic narrative of this wonder, and always will be. And it can be truly appreciated only once the reunification has been accomplished.

Germany and Italy have already returned fragments from the Parthenon to Athens. Britain should do its part, out of an impulse toward restoration in the most generous sense. Hitchens, as he often did, got the tone just right:

“There is still time to make the act of restitution: not extorted by pressure or complaint but freely offered as a homage to the indivisibility of art and—why not say it without embarrassment?—of justice too.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ralph Leonard

Ralph Leonard is a British-Nigerian writer on international politics, religion, culture and humanism.

What Christopher Hitchens Understood About the Parthenon

The British Museum should return the ancient treasures to Greece for the sake of art, not nationalism.

Everyone knows what a perversion fragmenting the Taj Mahal would be. We wouldn’t appreciate it with the awe we currently do as the “frozen music” (as Goethe once defined architecture) of Indo-Islamic design. We would be impatient to see what it would look like with its dome reattached—and in Agra, India, for only there can you properly see its marvelous proportions and appreciate the way the marble interacts with the light and the reflecting pools, changing hue depending on the time of day. This nearly magical experience couldn’t be re-created in, say, Manchester.

Σαν χιούμορ αυτό ξεπερνάει ακόμα και τα όρια της αγγλικής δηκτικότητας.

Σαν χιούμορ αυτό ξεπερνάει ακόμα και τα όρια της αγγλικής δηκτικότητας.