Είδα σήμερα κάπου να γράφουν Παταγωνία. Το Ορθογραφικό Λεξικό (ΟΛΝΕΓ) δεν περιλαμβάνει τη λέξη. Θα μπορούσα να φανταστώ σημείωση που θα έλεγε ότι προτιμούμε τη γραφή με –ω– επειδή μας θυμίζει τη Λακωνία. Γι’ αυτό άλλωστε γράφαμε ή γράφουμε και Καταλωνία. Οι εγκυκλοπαίδειές μου, τόσο η παλιά του Δρανδάκη όσο και η νεότερη του Πάπυρου, δεν βλέπουν το λόγο για το –ω– και γράφουν Παταγονία. Ωστόσο, οι εκδόσεις Χατζηνικολή θεώρησαν σκόπιμο να κυκλοφορήσουν τα δύο βιβλία του Τσάτγουιν με τη γραφή Παταγωνία. Υποθέτω ότι πείστηκαν από τον Τσάτγουιν ότι η λέξη έχει ελληνική προέλευση.

Για να καταλάβετε τι εννοώ, θα πρέπει να διαβάσετε την αρχή από το κεφάλαιο 49 τού In Patagonia του Bruce Chatwin και στη συνέχεια ένα πλαίσιο από την Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Growth and Development.

From the ship they saw a giant dancing naked on the shore, ‘dancing and leaping and singing, and, while singing, throwing sand and dust on his head’. As the white men approached, he raised one finger to the sky, questioning whether they had come from heaven. When led before the Captain-General, he covered his nakedness with a cape of guanaco hide.

The giant was a Tehuelche Indian, his people the race of copper-skinned hunters, whose size, strength and deafening voices belied their docile character (and may have been Swift’s model for the coarse but amiable giants of Brobdingnag). Magellan’s chronicler, Pigafetta, says they ran faster than horses, tipped their bows with points of silex, ate raw flesh, lived in tents and wandered up and down ‘like the Gipsies’.

The story goes on that Magellan said: ‘Ha! Patagon!’ meaning ‘Big-Foot’ for the size of his moccasins, and this origin for the word ‘Patagonia’ is usually accepted without question. But though pata is ‘a foot’ in Spanish, the suffix gon is meaningless. πάταγος, however, means ‘a roaring’ or ‘gnashing of teeth’ in Greek, and since Pigafetta describes the Patagonians ‘roaring like bulls’, one could imagine a Greek sailor in Magellan’s crew, a refugee perhaps from the Turks.

I checked the crew lists but could find no record of a Greek sailor. Then Professor Gonzales Díaz of Buenos Aires drew my attention to Primaleon of Greece, a romance of chivalry, as absurd as Amadis of Gaul and equally addictive. It was published in Castille in 1512, seven years before Magellan sailed. I looked up the English translation of 1596 and, at the end of Book II, found reason to believe that Magellan had a copy in his cabin:

The Knight Primaleon sails to a remote island and meets a cruel and ill-favoured people, who eat raw flesh and wear skins. In the interior lives a monster called the Grand Patagon, with the ‘head of a Dogge’ and the feet of a hart, but gifted with human understanding and amorous of women. The islanders’ chief persuades Primaleon to rid them of the terror. He rides out, fells the Patagon with a single sword thrust, and trusses him up with the leash of his two pet lions. The Patagon dyes the grass red with blood, roars ‘so dreadfully that it would have terrified the very stoutest hearte’, but recovers and licks his wound clean ‘with his huge broade tongue’.

Primaleon then decides to ship the creature home to Polonia to add to the royal collection of curiosities. On the voyage the Patagon cringes before his new master, and on landing Queen Gridonia is on hand to inspect him. ‘This is nothing but a devil,’ she says. ‘He gets no cherishing at my hands.’ But her daughter, the Princess Zephira, strokes the monster, sings to him and teaches him her language, while he ‘delights to gaze a fair lady in the face’ and follows ‘as gently as if he had been a spaniell’.

(Ακολουθούν οι εικασίες του Τσάτγουιν για το πώς ο Patagón μπορεί να υπήρξε η έμπνευση για τον Κάλιμπαν της Τρικυμίας του Σέξπιρ.)

Και από την Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Growth and Development (σελ. 390):

PATAGONIAN GIANTS: MYTHS AND POSSIBILITIES

When Magellan first arrived near San Julian in Patagonia, he is supposed to have cried ‘ho, patagon!’ but it is not clear what he saw or what he meant by this statement. However, this part of the earth has since been called Patagonia, and legends have arisen about its past inhabitants. In 1511, Francisco Vazquez published Palmeria de olivo, and in 1512 the second volume appeared at Salamanca. It was called Primaleon, a fantastic story about the knight Primaleon which was very popular at that time. Primaleon sails to a far-off island where he meets a wild population of ‘Patagonians’. He fights against a horrible giant beast, named the ‘Big Patagon’, overwhelms it, brings it to his ship and sails back to Polonia to present it to Queen Gridonia and her daughter Zerfira.

Magellan might well have known that story. When he discovered Patagonia, he found it populated with Tehuelche Indians, who are extinct now, but used to be of enormous size. According to Oviedo in 1520, Magellan estimated their stature ‘doce a trece palmos (12-13 times 21cm) de altura’, and Pigafetta wrote that ‘our heads just reached their hips’. In 1579 Sarmiento described ‘colosos de tres yarns (three times 83 cm)’, and in 1592, Knivet estimated their stature even 15-16 spans of the hand, whereas Hawkins did not measure at all, but simply called them giants (1593). Lemaire and Schouten measured them at 10 to 11 feet (1615), while Carman described them at 9 to 10 feet (1704). [Captain] Byron found the tallest to be 7 English feet and more, the smallest at least 6 feet, 6 inches. Bougainville (1767) measured them at between 5 French feet, 8 inches, to 6 feet, 4 inches, and Wallis (1767) found statures between 6 English feet, 7 inches, and 5 feet, 10 inches. Despite the great variation in reported height, all agree in that they were a tall population.

The current view is that mean adult male height may have been 173 centimetres, with a few individuals as tall as 192 centimetres, and a mean female height of 162 centimetres. This makes them taller than any contemporary Asiatic population, however wealthy, but shorter than many European, and European-origin populations […] The Tehuelche Indians disappeared in the middle of the 19th century, and what is left are single bones of impressive size in the Museo Regional Provincial ‘Padre Manuel Jesus Molina’ at Rio Gallegos. Magellan’s chronicle told that one of these Patagonians was caught and brought into Magellan’s ship, just as the knight Primaleon did with the Big Patagon. It may be that Magellan had this story in mind when he cried ‘ha, patagon!’.

Michael Hermanussen

Δείτε και: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patagonia

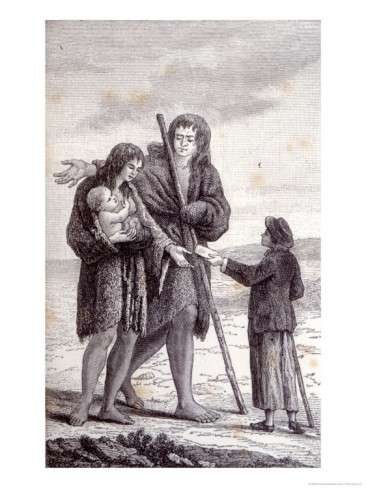

E. Garnier’s drawing of Captain Byron’s encounter with giants in Patagonia, from Nains et géants (1964-5).

The caption reads: ‘An English sailor giving a biscuit to a Patagonian woman.’

Για να καταλάβετε τι εννοώ, θα πρέπει να διαβάσετε την αρχή από το κεφάλαιο 49 τού In Patagonia του Bruce Chatwin και στη συνέχεια ένα πλαίσιο από την Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Growth and Development.

49

Bernal Díaz relates how, on seeing the jewelled cities of Mexico, the Conquistadores wondered if they had not stepped into the Book of Amadis or the fabric of a dream. His lines are sometimes quoted to support the assertion that history aspires to the symmetry of myth. A similar case concerns Magellan’s landfall at San Julian in 1520: From the ship they saw a giant dancing naked on the shore, ‘dancing and leaping and singing, and, while singing, throwing sand and dust on his head’. As the white men approached, he raised one finger to the sky, questioning whether they had come from heaven. When led before the Captain-General, he covered his nakedness with a cape of guanaco hide.

The giant was a Tehuelche Indian, his people the race of copper-skinned hunters, whose size, strength and deafening voices belied their docile character (and may have been Swift’s model for the coarse but amiable giants of Brobdingnag). Magellan’s chronicler, Pigafetta, says they ran faster than horses, tipped their bows with points of silex, ate raw flesh, lived in tents and wandered up and down ‘like the Gipsies’.

The story goes on that Magellan said: ‘Ha! Patagon!’ meaning ‘Big-Foot’ for the size of his moccasins, and this origin for the word ‘Patagonia’ is usually accepted without question. But though pata is ‘a foot’ in Spanish, the suffix gon is meaningless. πάταγος, however, means ‘a roaring’ or ‘gnashing of teeth’ in Greek, and since Pigafetta describes the Patagonians ‘roaring like bulls’, one could imagine a Greek sailor in Magellan’s crew, a refugee perhaps from the Turks.

I checked the crew lists but could find no record of a Greek sailor. Then Professor Gonzales Díaz of Buenos Aires drew my attention to Primaleon of Greece, a romance of chivalry, as absurd as Amadis of Gaul and equally addictive. It was published in Castille in 1512, seven years before Magellan sailed. I looked up the English translation of 1596 and, at the end of Book II, found reason to believe that Magellan had a copy in his cabin:

The Knight Primaleon sails to a remote island and meets a cruel and ill-favoured people, who eat raw flesh and wear skins. In the interior lives a monster called the Grand Patagon, with the ‘head of a Dogge’ and the feet of a hart, but gifted with human understanding and amorous of women. The islanders’ chief persuades Primaleon to rid them of the terror. He rides out, fells the Patagon with a single sword thrust, and trusses him up with the leash of his two pet lions. The Patagon dyes the grass red with blood, roars ‘so dreadfully that it would have terrified the very stoutest hearte’, but recovers and licks his wound clean ‘with his huge broade tongue’.

Primaleon then decides to ship the creature home to Polonia to add to the royal collection of curiosities. On the voyage the Patagon cringes before his new master, and on landing Queen Gridonia is on hand to inspect him. ‘This is nothing but a devil,’ she says. ‘He gets no cherishing at my hands.’ But her daughter, the Princess Zephira, strokes the monster, sings to him and teaches him her language, while he ‘delights to gaze a fair lady in the face’ and follows ‘as gently as if he had been a spaniell’.

(Ακολουθούν οι εικασίες του Τσάτγουιν για το πώς ο Patagón μπορεί να υπήρξε η έμπνευση για τον Κάλιμπαν της Τρικυμίας του Σέξπιρ.)

Και από την Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Growth and Development (σελ. 390):

PATAGONIAN GIANTS: MYTHS AND POSSIBILITIES

When Magellan first arrived near San Julian in Patagonia, he is supposed to have cried ‘ho, patagon!’ but it is not clear what he saw or what he meant by this statement. However, this part of the earth has since been called Patagonia, and legends have arisen about its past inhabitants. In 1511, Francisco Vazquez published Palmeria de olivo, and in 1512 the second volume appeared at Salamanca. It was called Primaleon, a fantastic story about the knight Primaleon which was very popular at that time. Primaleon sails to a far-off island where he meets a wild population of ‘Patagonians’. He fights against a horrible giant beast, named the ‘Big Patagon’, overwhelms it, brings it to his ship and sails back to Polonia to present it to Queen Gridonia and her daughter Zerfira.

Magellan might well have known that story. When he discovered Patagonia, he found it populated with Tehuelche Indians, who are extinct now, but used to be of enormous size. According to Oviedo in 1520, Magellan estimated their stature ‘doce a trece palmos (12-13 times 21cm) de altura’, and Pigafetta wrote that ‘our heads just reached their hips’. In 1579 Sarmiento described ‘colosos de tres yarns (three times 83 cm)’, and in 1592, Knivet estimated their stature even 15-16 spans of the hand, whereas Hawkins did not measure at all, but simply called them giants (1593). Lemaire and Schouten measured them at 10 to 11 feet (1615), while Carman described them at 9 to 10 feet (1704). [Captain] Byron found the tallest to be 7 English feet and more, the smallest at least 6 feet, 6 inches. Bougainville (1767) measured them at between 5 French feet, 8 inches, to 6 feet, 4 inches, and Wallis (1767) found statures between 6 English feet, 7 inches, and 5 feet, 10 inches. Despite the great variation in reported height, all agree in that they were a tall population.

The current view is that mean adult male height may have been 173 centimetres, with a few individuals as tall as 192 centimetres, and a mean female height of 162 centimetres. This makes them taller than any contemporary Asiatic population, however wealthy, but shorter than many European, and European-origin populations […] The Tehuelche Indians disappeared in the middle of the 19th century, and what is left are single bones of impressive size in the Museo Regional Provincial ‘Padre Manuel Jesus Molina’ at Rio Gallegos. Magellan’s chronicle told that one of these Patagonians was caught and brought into Magellan’s ship, just as the knight Primaleon did with the Big Patagon. It may be that Magellan had this story in mind when he cried ‘ha, patagon!’.

Michael Hermanussen

Δείτε και: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patagonia

E. Garnier’s drawing of Captain Byron’s encounter with giants in Patagonia, from Nains et géants (1964-5).

The caption reads: ‘An English sailor giving a biscuit to a Patagonian woman.’