Γράφει ο Γ. Γιατρομανωλάκης στο προχτεσινό Βήμα:

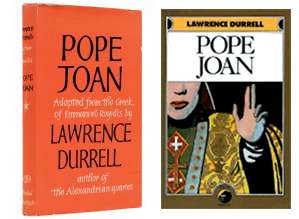

Όχι από λάθος. Για να πουλήσει. Ενώ στις περισσότερες άλλες εκδόσεις (εγώ έχω τη σκληρόδετη, αριστερά) το όνομα του μεταφραστή και διασκευαστή είναι με μεγάλα γράμματα, πάντα με προβολή μεγαλύτερη από το όνομα του συγγραφέα, στην έκδοση που βλέπω ότι κυκλοφορεί τώρα το όνομα του συγγραφέα έχει εξαφανιστεί εντελώς από το εξώφυλλο.

Δείτε εντυπώσεις αναγνωστών για το βιβλίο:

http://www.amazon.com/Pope-Joan-Emmanual-Royidis/dp/0879517867

Κριτική:

http://www.medievalists.net/2011/12/29/book-review-pope-joan-by-lawrence-durrell/

Ισπανική μετάφραση από τη μετάφραση:

http://www.uniliber.com/ficha.php?id=796686

Η Πάπισσα Ιωάννα ως Π.Ο.Π.

Η τραγελαγική (sic) ιστορία που επί 60 χρόνια θέλει ως συγγραφέα της «Πάπισσας Ιωάννας» τον μεταφραστή της Lawrence Durrell και όχι τον Εμμανουήλ Ροΐδη, χωρίς ποτέ κάποιος από εμάς να διαμαρτυρηθεί, δεν είναι η ίδια ιστορία με τα λεγόμενα «ελγίνεια». Όλοι θυμόμαστε με πόσο σθένος ο πρώην Υπουργός Πολιτισμού, ακολουθώντας τον George Clooney, διαμαρτυρήθηκε για τα «Μάρμαρα». Και όπως πάντα όλοι μας χαρήκαμε. Όμως για τον πολλάκις υβρισμένο και καταδιωγμένο Ε. Ροΐδη καμιά διαμαρτυρία γι αυτή την ανίερη παρανόηση. Ούτως ή άλλως η νεοελληνική πεζογραφία δεν πουλάει, όπως η φέτα και άλλα προστατευόμενα προϊόντα (Π.Ο.Π). Για τούτο ούτε καν μας ενδιαφέρει αν η ανατρεπτική «Πάπισσα» εμφανίζεται διεθνώς (προφανώς από λάθος) ως έργο του μεταφραστή της.

http://www.tovima.gr/opinions/article/?aid=615993

Η τραγελαγική (sic) ιστορία που επί 60 χρόνια θέλει ως συγγραφέα της «Πάπισσας Ιωάννας» τον μεταφραστή της Lawrence Durrell και όχι τον Εμμανουήλ Ροΐδη, χωρίς ποτέ κάποιος από εμάς να διαμαρτυρηθεί, δεν είναι η ίδια ιστορία με τα λεγόμενα «ελγίνεια». Όλοι θυμόμαστε με πόσο σθένος ο πρώην Υπουργός Πολιτισμού, ακολουθώντας τον George Clooney, διαμαρτυρήθηκε για τα «Μάρμαρα». Και όπως πάντα όλοι μας χαρήκαμε. Όμως για τον πολλάκις υβρισμένο και καταδιωγμένο Ε. Ροΐδη καμιά διαμαρτυρία γι αυτή την ανίερη παρανόηση. Ούτως ή άλλως η νεοελληνική πεζογραφία δεν πουλάει, όπως η φέτα και άλλα προστατευόμενα προϊόντα (Π.Ο.Π). Για τούτο ούτε καν μας ενδιαφέρει αν η ανατρεπτική «Πάπισσα» εμφανίζεται διεθνώς (προφανώς από λάθος) ως έργο του μεταφραστή της.

http://www.tovima.gr/opinions/article/?aid=615993

Όχι από λάθος. Για να πουλήσει. Ενώ στις περισσότερες άλλες εκδόσεις (εγώ έχω τη σκληρόδετη, αριστερά) το όνομα του μεταφραστή και διασκευαστή είναι με μεγάλα γράμματα, πάντα με προβολή μεγαλύτερη από το όνομα του συγγραφέα, στην έκδοση που βλέπω ότι κυκλοφορεί τώρα το όνομα του συγγραφέα έχει εξαφανιστεί εντελώς από το εξώφυλλο.

Δείτε εντυπώσεις αναγνωστών για το βιβλίο:

http://www.amazon.com/Pope-Joan-Emmanual-Royidis/dp/0879517867

Κριτική:

http://www.medievalists.net/2011/12/29/book-review-pope-joan-by-lawrence-durrell/

Ισπανική μετάφραση από τη μετάφραση:

http://www.uniliber.com/ficha.php?id=796686